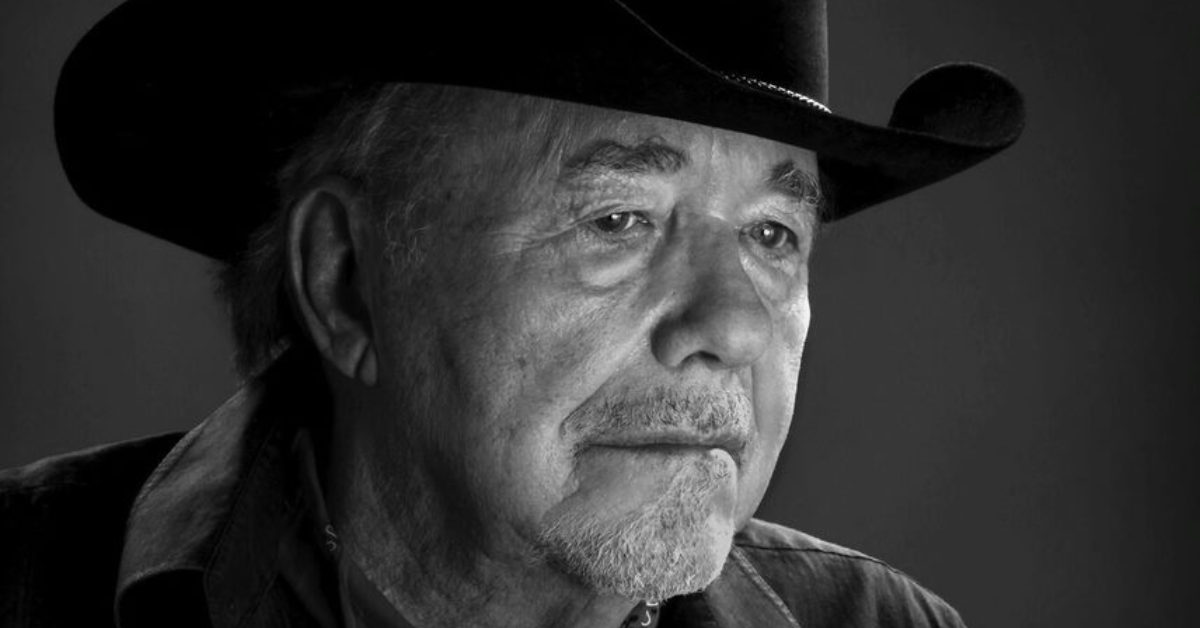

Bobby Bare

Artist Videos

Artist Information

Bobby Bare scored nearly five dozen top 40 hits from 1962 to 1983. In a laconic vocal style that embraces both wry country wit and poignant folk storytelling, his literate, cross-cultural appeal has earned him the sobriquet "the Springsteen of country."

Born Robert Joseph Bare in Ironton, Ohio, he had a rough early life. "Well, my mother died when I was five," he told the author of Country Music Changed My Life. "That was in early '41. I had two sisters, one was seven, one was two. My dad couldn't take care of all us. So my younger sister was adopted to some people who lived down the road. Then, my other sister stayed with my grandparents and different relatives." To cope with the unease of being shifted around so much, the youngster dreamed of being a country singer and even made his first guitar. "Yeah. I'd get me a coffee can, put a flat stick in it, get some screen wires to make some strings—your imagination really works good when you're young," he laughed before adding, "It sounded like s**t."

Although he lived and worked on a farm, Bare picked up some surprisingly eclectic musical influences during his youth. "We didn't have any rock 'n' roll or other country, really all we had was the Grand Ole Opry, that was my favorite," Bare recalled, "but I always listened to the big bands of the '40s and I liked different songs—Phil Harris singing 'That's What I Like about the South,' the Dominoes doing 'Sixty Minute Man'—I loved that song. I found out later that was Shel Silverstein's favorite song too. And then, of course, there came Hank Williams, Carl Smith, Webb Pierce, Hank Thompson, and Little Jimmy Dickens. I loved all of that, still do. The first song I ever sang in public was one of Little Jimmy Dickens' 'Sleepin' at the Foot of the Bed."

By his own account a bright student—he was in eighth grade at age eleven—Bare never finished his education. "I couldn't get along with my stepmother," he explained. "So, I left home and stayed with my grandmother, my aunts and my uncles, and put a little band together." He was still a teenager when he and his first group began playing on an early morning radio show in and around Springfield, Ohio. Eventually he parlayed that experience into a much better weekly radio gig approximately 59 miles away in Wilston. "Looking back, I was really hot. We were broadcasting live from a radio station which was a farm house out in the middle of a field. This was before TV completely took over in about '52 or '53. On Saturday afternoons, it wasn't unusual to look out the window of the radio station while we were broadcasting and see a hundred cars parked in that field watching the farm house."

After figuring that he had gone as far as he could in Ohio, Bare got a ride to the West Coast with a man who claimed to know famed country instrumentalists Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West. "The reason he wanted us to go was because he didn't have any money and he needed someone to pay for gas," Bare recalled with a chuckle. After an adventurous ride that necessitated playing for tips to raise gas money, the singer arrived in California to a pleasant surprise: "[I]t turns out this old boy we were riding with really did know Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West," chuckled Bare. "Speedy loved my singing and started taking me around. I wrote songs for his publishing company, met Cliffie Stone, and I'd do his radio show.... Speedy was the one who got me a record deal with Capitol."

First Hit under Another Name:

<p>Recording for legendary producer Ken Nelson (who worked with Wanda Jackson, Buck Owens, Gene Vincent, etc.), Bare's future seemed assured. However, the young singer's first country single—a cover of Buck Owens's "Down on the Corner of Love"—stiffed, so Nelson and Capitol decided to make his next outing a rockabilly record. "That didn't work," Bare told this writer. "I did one thing called <em>The Living End</em> and <em>I Beg Her.</em> They weren't very good records."</p>Rebuffed when Nelson wouldn't let him pursue his own musical ideas, Bare asked for his release from Capitol so he could sign with the relatively small Challenge label. There he recorded with his friends the Champs (of "Tequila" fame), but these sides—released on the Jackpot subsidiary—didn't click either. Friend and country legend Wynn Stewart helped keep him housed and employed in California clubs, but just as he was making headway in his own nightspot, he received his draft notice.

Back in Ohio awaiting induction, Bare ran into his friend Bill Parsons who was just being discharged from the Army. Parsons wanted a record deal and Bare advised him to cut some demos. "So, we got some musicians off the streets of Dayton, Ohio, I was staying there with my sister, and got this old boy who bought the club I used to work in—his name was Cherokee—and he wanted to be in the record business," Bare recalled. "So, he was paying for the studio time and the musicians. We went to King Records in Cincinnati and did some demos, spent most of the three hours working on a thing called 'Rubber Dolly,' with Bill [Parsons] singing it. In the meantime, I was making up this talking blues song about going into the army. We had 15 minutes left and I said, 'Let me put this down real quick so I don't forget it.' So, I did. That was 'The All-American Boy.' Cherokee, who was paying for all of it, wanted to get a copy made but Syd Nathan was revamping his studio then and had all of his equipment tore down—his copy machines and everything. So, he suggested that maybe Harry Carlson of Fraternity Records and Cincinnati could make a copy off that tape. Bill and I went back up to Dayton to a bar we used to hang out in and Cherokee went down to the record company to get an acetate made and they heard it and wanted to put it out. While he was there, he called us at the club and said that they had offered him 500 bucks, I said, 'Hell, take it. Just don't put my name on it.'"

The next time Bare heard "The All-American Boy" was during his basic training stint at Fort Knox. By the time he came home on leave, the satirical allusion to both his and Elvis Presley's rise to fame and subsequent army hitch was one of the hottest records in the country, hitting number two on the pop charts in 1959. Fraternity had put Bill Parsons's name on the label—since Bare was still under contract to Challenge—and had him lip-synch the record on tour. Although he never received any royalties for the song, Bare didn't begrudge his friend the hit. "No. No, not at all," Bare stated. "Fact is, it was really good that my name wasn't on that record. Because then I probably wouldn't have had any serious hits like 'Detroit City.' I would've been pegged as a novelty type guy."

Became a Star at RCA:

During his two-year army hitch, Bare entered several talent competitions and even appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show with an instrumental combo called the Latin Five. By then Fraternity had discovered that it was his voice on their biggest hit and began recording sides crediting Bare on the label. (All of Bare's Capitol, Challenge, and Fraternity sides are included on the 1994 Bear Family boxed set All American Boy.) None became hits, but he recalls that the Barry DeVorzan-produced "Book of Love" was a near-miss in 1961. Bare recorded three songs for the Jimmy Clanton teen flick Teenage Millionaire, but the singer-songwriter, who ached to record his version of country music, was floundering at Fraternity, a fact not lost on his friends. "I made records for about a year or so for Fraternity," explained Bare, "by then all my friends that I started out with in California—Harlan Howard, Hank Cochran, and all them people had moved back [to Nashville], and became really successful.... But, they all ganged up and told [RCA vice-president and guitarist extraordinaire] Chet [Atkins] how great I was and he wanted to meet me. So, I met Chet who said, 'Come back in a week and we'll have you a contract and look for songs, cut you a record.'"

At RCA, Atkins was willing to listen to Bare's ideas. When the singer wanted to use horns on a country record—a first for Nashville—and strings, the producer made it happen. The result was Bare's breakout hit "Shame On Me." Better still was his Grammy-winning rendition of the Mel Tillis and Danny Dill-penned "Detroit City," which became a classic anthem for displaced southerners everywhere. "I heard Billy Grammer's record of 'Detroit City' while I was driving down the street one day and I damn near wrecked my car," laughed Bare. "I thought it was the greatest song I ever heard in my life."

During his early period with RCA, Bare's records seemed as much folk as country. "That was just the taste I had in songs at the time," the singer explained. "I wrote '500 Miles Away From Home,' that's an old folk song. Me and Don Bowman were driving back home from San Diego one night when I lived in California and I heard Peter, Paul, & Mary sing that and I said, 'Godd**n that's great!' I remembered that title—Glen Campbell lived right down the street from me at the time, and he had just done a bluegrass album or something with [an instrumental version of] that in it and brought it to me. So, I just wrote a new set of lyrics and recorded it."

Bare's music became increasingly country with such hits as "Miller's Cave" and "Four Strong Winds" and he became a regular, if not overwhelming, presence in that genre's top 40. He used his power as a hitmaker to introduce his friend Waylon Jennings to RCA, and to craft unusual projects such as the narrative-oriented Bird Named Yesterday. By decade's end, he'd scored a major hit with his former bass player Tom T. Hall's song, "(Maggie's at) The Lincoln Park Inn," which shocked listeners with its matter-of-fact approach to adultery. Despite the controversial hit, which he was not allowed to sing on a scheduled American Bandstand appearance, Bare's career had obviously cooled.

Worked with Shel Silverstein:

In 1970, Bare switched to Mercury Records where he recorded Tom T. Hall's "How I Got To Memphis," along with Kris Kristofferson's "Come Sundown," and "Please Don't Tell Me How the Story Ends." Keenly appreciative of the great country songwriters, he produced albums on such legendary songsmiths as Harlan Howard, Mickey Newberry, and Billy Joe Shaver. That said, the songwriter most in tune with his own sensibilities was Shel Silverstein.

"Well, I loved Shel's songs before I even knew he wrote them," Bare disclosed. "Years ago I heard Burl Ives singing a song on TV called, 'Time.' I had no idea that Shel wrote that but I loved that song, eventually I cut it a couple of times. Once I was in Europe and I heard Marianne Faithfull sing 'The Ballad of Lucy Jordan,' and I said, 'God, that's great!' I found out years later that Shel wrote that. Then, of course, I heard 'Sylvia's Mother,' and I thought, 'Man that's great!' Anyway, Shel is the greatest lyricist there ever was."

Silverstein figured prominently upon Bare's return to RCA where he wrote what many have claimed to be the first country music concept album, Lullabys, Legends & Lies, (1973) which contained the singer's duet with his five-year old son Bobby, Jr., "Daddy What If" and his lone chart-topper "Marie Laveau." Another popular and witty Silverstein—Bare collaboration was the Grammy-nominated Singin' in the Kitchen which sported a catchy, informal family sing-along atmosphere. Many other Silverstein songs figured prominently during Bare's renewed chart run, most notably "The Winner" and the controversial "Drop Kick Me, Jesus (Through the Goalposts of Life)," the latter said to be former President Clinton's favorite song.

Dubbed the Springsteen of Country:

Due to his outsider stance and willingness to record material by Bob Dylan, Townes Van Zandt, and the Rolling Stones, Bare has always had credibility with rock audiences. Acknowledging his ability to convey a song's story, famed promoter Bill Graham christened Bare the "Bruce Springsteen of country" in 1977. One of the few country veterans to regularly receive airplay on FM rock radio, he garnered a surprisingly strong following among college audiences of the era.

Bare's final important chart singles came at Columbia Records where he nearly cracked the country top ten with "Sleep Tight, Good Night Man," and "Numbers," which both hit number eleven in 1978. Equally fine was his duet with Roseanne Cash "No Memories Hangin' Around." Although Bare had done much to widen the parameters of mainstream country music, radio playlists couldn't find room for his work during the neotraditional 1980s. A few of his EMI singles dented the bottom of the charts and he hosted his own talk show on TNN, but his career devolved to a largely leisure-time activity.

A notable exception came when he teamed with friends Waylon Jennings, Jerry Reed, and Mel Tillis for an album of geriatric country comedy called Old Dogs. Shel Silverstein penned all the songs. "We spent about a year in the studio working on that," recalled Bare. "We had a ton of fun. That's the last thing Shel ever did. I was just devastated when he died.... It just floored me because he was the last one I expected to go. He was the only one of all my friends who took care of himself.... With most of my other friends, you could see it coming. With Chet, I could see that coming for two or three years at least. With Cliffie Stone, I could see that coming ... And, Harlan [Howard], I didn't expect him to last as long as he did because he drank so hard there at the end. Waylon, we knew that was coming. But with Shel, we weren't ready for that, we were blindsided."

The early 2000s found Bare playing country legends tours, casino dates, and doing as much fishing as he desired. Yet, he still occasionally dabbles in music, guesting on the eclectic alt. rock/country albums of his son, Bloodshot recording artist Bobby Bare, Jr. Asked if he has been able to advise his son's career, Bare chuckles with pride, "It's a brand new ballgame what he's doing. My phrase to him was, 'Son, I can't help you with this.'"

Similar Artists

Stay In Touch

It's our biggest year yet! Don't miss any Opry 100 announcements, events, and exclusive offers for fans like you. Sign up now!